The Backside of Yesteryear

The first time Clarke Otte combined his love of Thoroughbreds and photography was in 1958, when he drove to Standiford Field and waited for a horse called Silky Sullivan to disembark a plane. He’d been following the Santa Anita Derby winner closely and was excited to have him in town to train at Churchill Downs for the Kentucky Derby. Silky Sullivan’s trainer, Reggie Cornell, agreed to let Clarke take some pictures. Clarke got some good shots, and Cornell bought 25 copies to circulate among the Silky Sullivan fan club. (Silky, one of the favorites, finished 12th; Tim Tam won.)

The little German film camera Clarke used, a Zeiss Ikon, had an interesting provenance. Clarke’s father was the Commonwealth’s attorney in the early 1930s, but by the time Clarke was born, his dad had switched sides and was working as a successful defense attorney. One of his clients, a distinguished-looking professional hotel thief, once came by the Otte home on Eastern Parkway bearing a gift — the Zeiss Ikon — for Clarke’s mother, who later gave it to him. It went largely unused until after high school in the 1950s, when he dug it out to go take those pictures of Silky Sullivan.

Horse racing and photography would become two of the pillars of Clarke’s life. He started working in racing and went on the circuit doing most every job on the backside. Through the ’60s and ’70s, he kept the camera around and, during his travels, would take pictures of the horses he admired and the people who cared for them. I’ve looked at probably a thousand Clarke Otte photos and am consistently struck by his admiration for his subjects. Clarke, now 86, likes people, and people like him. When I visit him in the Cloverleaf neighborhood in southwest Louisville, our conversations are wide-ranging and engaging. We lose hours talking about religion, family and Clarke’s love of racing.

Fast-forward to a few years ago: The Louisville Story Program, where I’m deputy director, was halfway through a three-year project to publish a book documenting the Churchill Downs backside — the gated and cloistered stable area where 1,000 people come to work every day during a busy racing meet. To be authored by the very people who work there and live in the adjacent neighborhoods. The backside community is, by its very design, out of sight, and most of us understand precious little about the lives of the grooms, hotwalkers, exercise riders, outriders, security guards, assistants, educators and raconteurs who make up the real heartbeat of racing in Louisville, and who are also routinely overlooked amid the glitz and glam of Derby Week. It’s increasingly self-evident that, if we ever really care to understand our city, ourselves and the legacy of Thoroughbred racing here, we must listen to the folks who make racing possible. We hoped the book, published in 2019, could play some small role in filling in the gaps.

Breaking into the backside’s tight-knit and cloistered community wasn’t easy. Come to find out, racetrackers can be a little buttoned up when asked to talk shop and tell their best tall tales into a live microphone. It took time and some mule-like persistence to become part of the scenery. One day, about halfway through the project, an acquaintance at the track said, “You know, my co-worker showed up with a box FULL of old photographs from the backside. Just old pictures of barn life back in the day. Maybe you’d be interested in some of them.” When I picked my jaw up off the floor, I assured them that, yes, I would like to see those pictures a great deal. The box of images would lead us to one Clarke Otte and to the central visual set pieces and tone of the book. But, just as important, Clarke’s pictures got us in the door many, many times.

When I had a stack of Clarke’s photos on hand — when prospective interview participants from the old-school set laid eyes on the warm palette of those candid shots from the Churchill Downs backstretch of yesteryear, when they saw the faces of their friends, some of them long passed, staring back at them — the stories flooded out. Our friends on the track were so thrilled to see these pictures that they’d holler at people across the track kitchen or over in the next barn: “Hey, man! You gotta come see this. Here’s a picture of Uncle Tommy and Willard.” The gratitude people felt when looking at the pictures translated into an erasure of suspicion about our project. It was like having a stack of goodwill in my back pocket.

We’ll never be able to thank Clarke for that service nearly enough.

Here are 10 of his photos, with captions drawn from him and other backside folks, who recalled memories while looking at the images.

— Joe Manning

“This is Bob and Gene Rice. They were brothers. That’s the Churchill Downs blacksmith shop. That’s where the farriers hung out.” — Clarke

“Willard Pinkston was one of the best exercise boys on the backside. I remember one time I was working for Suddie Whitaker; we called him Little Man. Uncle Willard and Little Man galloped this horse in the snow in the wintertime at Churchill to get him ready once. When they got him fit here galloping in the snow, they took him somewhere and he won by 15 lengths. He was the best. He could handle a mean horse. He was a good horseman. He raised me. I lived right next door to him.” — Catfish

“Tommy Long goes way back with Harthill. Way back. He ran a lot of horses for Doc (Harthill). Baylor Hickman was Doc’s father-in-law, and he owned a distillery in Canada. Hickman gave Tommy that car.” — Clarke (pictured left to right: Houston, Roy Dixon, Tommy Long, Beady, Red.)

“That’s Bimp on the end. My wife did his taxes. I don’t remember his real name. He worked for Calumet when he was younger. Then he went to work for International Harvester. Then he came over to the track and did some work for Arnold Werner. Next to him is Tommy Long. That’s Centerfield Slim. He got hit by a car and had one leg shorter than the other. He was a nightwatchman and did odd jobs. That was his little dog there. Angel Montano had a dog called Wino, and he’d come over because he liked Slim’s little dog. That’s a guy named Ferris there in the chair. He was a retired fireman and he’s probably waiting for one of these fellas to get free and help him with his horses.” — Clarke

“Mo and James Albert. They worked for Mike Law.” — Catfish

“In 1959 I was working for Sears giving roofing estimates. I was driving around down by the track after giving a bid and I saw Northern Dancer grazing over by Longfield Avenue. I’d seen him on TV and recognized him, those white stockings. He was a little horse, only about 15 hands. But he was well-muscled. I went back there and took this picture of Northern Dancer and his groom Willie Brevard.” — Clarke (Northern Dancer won the 1964 Kentucky Derby.)

“Papa Jim was from New Orleans. He worked for Louis Rousell there on Louisiana Downs racetrack. And he helped Harthill when he was down there in the ’82 or ’83 season. Harthill had a horse — Real Westport — that he was hoping to get to the Derby, but didn’t make it. He always had that cigar.” — Clarke

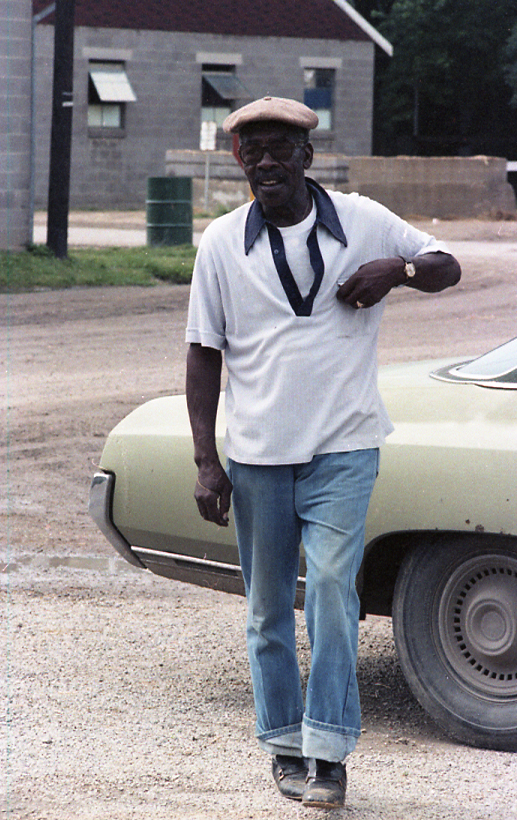

“Scotland Yard liked me and he kind of took care of me. Here he’s pulling a $10 winning ticket out of his pocket to show me. He was on to some horse. He was connected with everything and knew everything. That’s why they called him Scotland Yard. He had a real sharp line and could talk slick. You might say, ‘That guy’s lucky,’ and Yard would say, ‘He could fall out of a jet plane, shit through the eye of a needle and land on a haystack without a scratch.’” — Clarke

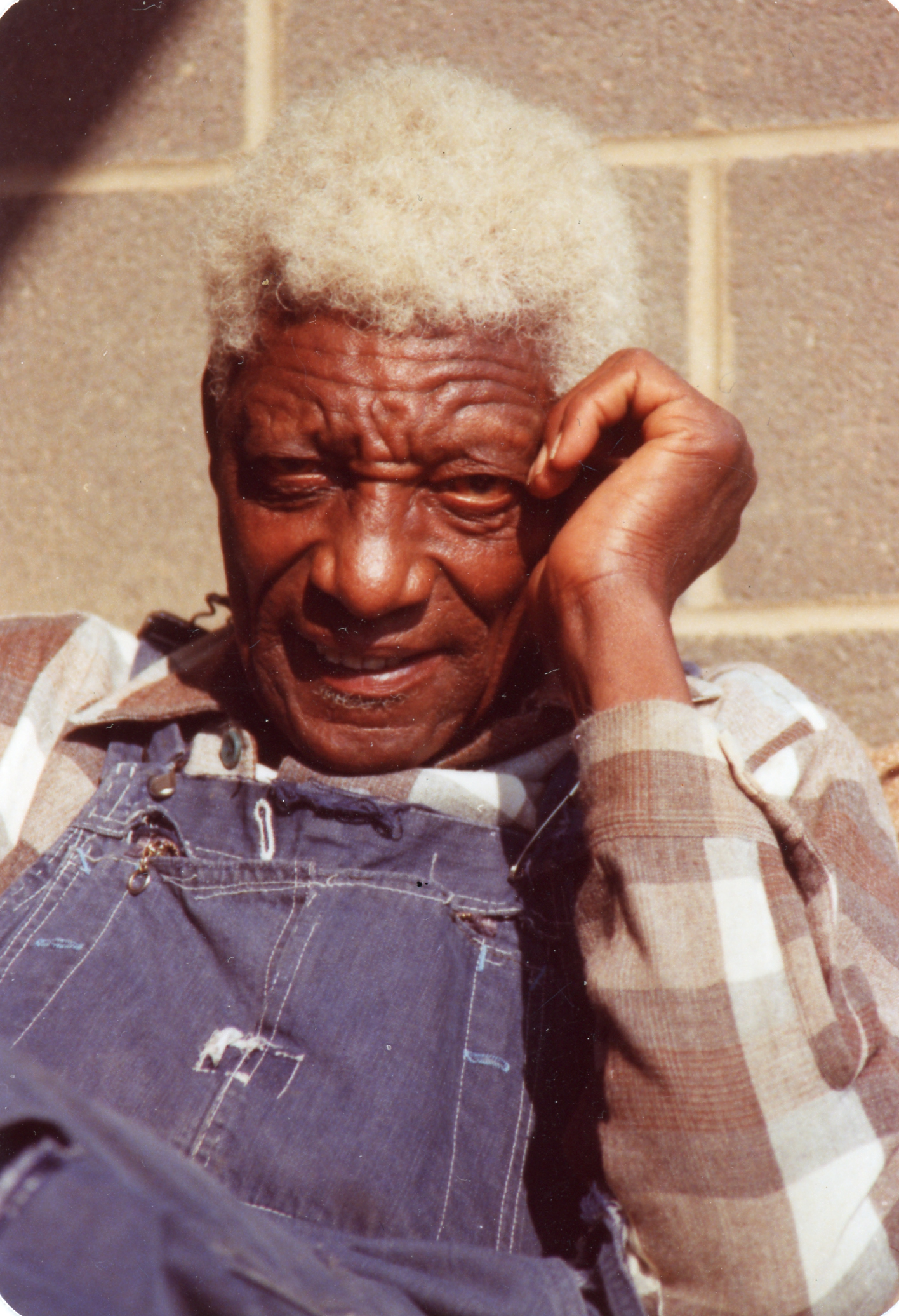

“Slim had one leg longer than the other. He was a good dude. He and my stepdaddy used to be drinking partners. They liked Old Forester and ET, Early Times. They were good horsemen.” — Catfish

“Everybody respected Tommy Long. White, Black, whatever — everybody respected him. Tommy was just a hell of a guy to be around. Just a pure horseman. Me and some friends started working with him when we were around 11 years old. He was more like a father to us than our fathers were. Tommy would come through the neighborhood and say, ‘What’re y’all boys doing? Let’s go. Get in the truck. We gonna go see some Thoroughbreds.’ Mom would say, ‘Where y’all going?’ And we would tell her we were with Uncle Tommy.” — Leonard “Plummie” Bass

Clarke’s first-person account of his life in racing, and those of many other racetrackers, can be found in the Louisville Story Program’s 2019 publication Better Lucky Than Good: Tall Tales and Straight Talk from the Backside of the Track. You can also check out the book’s podcast companion piece Track Changes, a collaboration between Louisville Story Program and Louisville Public Media.

Share This Article

We want to hear from you. Who or what should more Louisvillians know about? Share here.